Apala is a Yoruba percussion-driven genre from southwestern Nigeria, rooted in Muslim communities and praise-singing traditions.

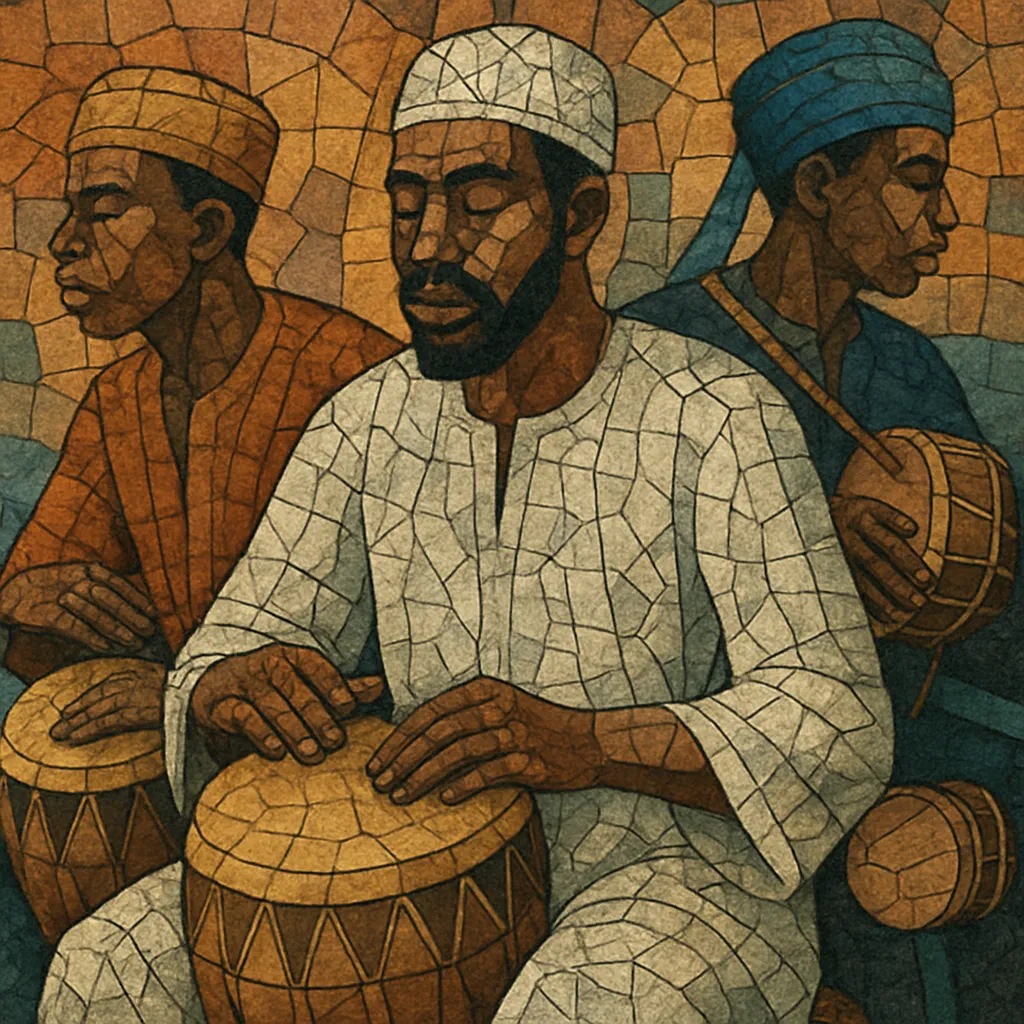

It features a lead vocalist delivering melismatic, proverb-rich lines answered by a chorus, all propelled by interlocking hand and stick percussion, the resonant agidigbo (a box lamellophone), shekere, and talking drums.

Apala’s rhythms are typically mid-tempo and swung (often in 12/8), prioritizing groove and timbral dialogue over harmonic movement. The music is socially embedded—performed at naming ceremonies, festivals, and during Ramadan dawn awakenings—where its poetic oriki (praise) lyrics, moral counsel, and social commentary take center stage.

Apala crystallized among the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria in the 1940s, drawing on older local percussion ensembles and Islamic devotional performance practices tied to Ramadan wake-up songs. Early groups standardized a core instrumentation (agidigbo, shekere, bells, talking drums, and supporting hand drums) and a performance format based on call-and-response, poetic praise, and improvisation. The first studio recordings in the 1950s—circulating on labels active in Lagos and the broader West African market—helped fix the ensemble sound and repertoire.

By the 1960s, Apala had matured into a distinct professional genre with star bandleaders and long-form recordings that showcased cyclic grooves, extended praise sections, and lyrical wit. Haruna Ishola and Ayinla Omowura became household names, refining vocal delivery and ensemble balance. In urban centers, Apala coexisted with juju and highlife but maintained its percussion-first aesthetic and Islamic-inflected vocal style. The 1970s brought wider radio play and touring circuits; at the same time, the genre remained rooted in community functions.

From the 1980s onward, Apala’s traditional format persisted through hereditary bands and family lineages (notably the Ishola family). While fuji—a related Yoruba Muslim style—surged in popular appeal, it absorbed rhythmic and vocal conventions from Apala. In the 2000s–2010s, younger artists and producers revisited Apala timbres in new contexts, sampling agidigbo patterns or adapting the swung 12/8 feel for contemporary Nigerian pop. This has fostered a modest revival and recontextualization—often branded as “new school” iterations—without abandoning the genre’s communal and praise-centered roots.