Ancient Egyptian music refers to the soundworld and performance practices of Egypt from the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods through the Ptolemaic era (ca. 3000–30 BCE).

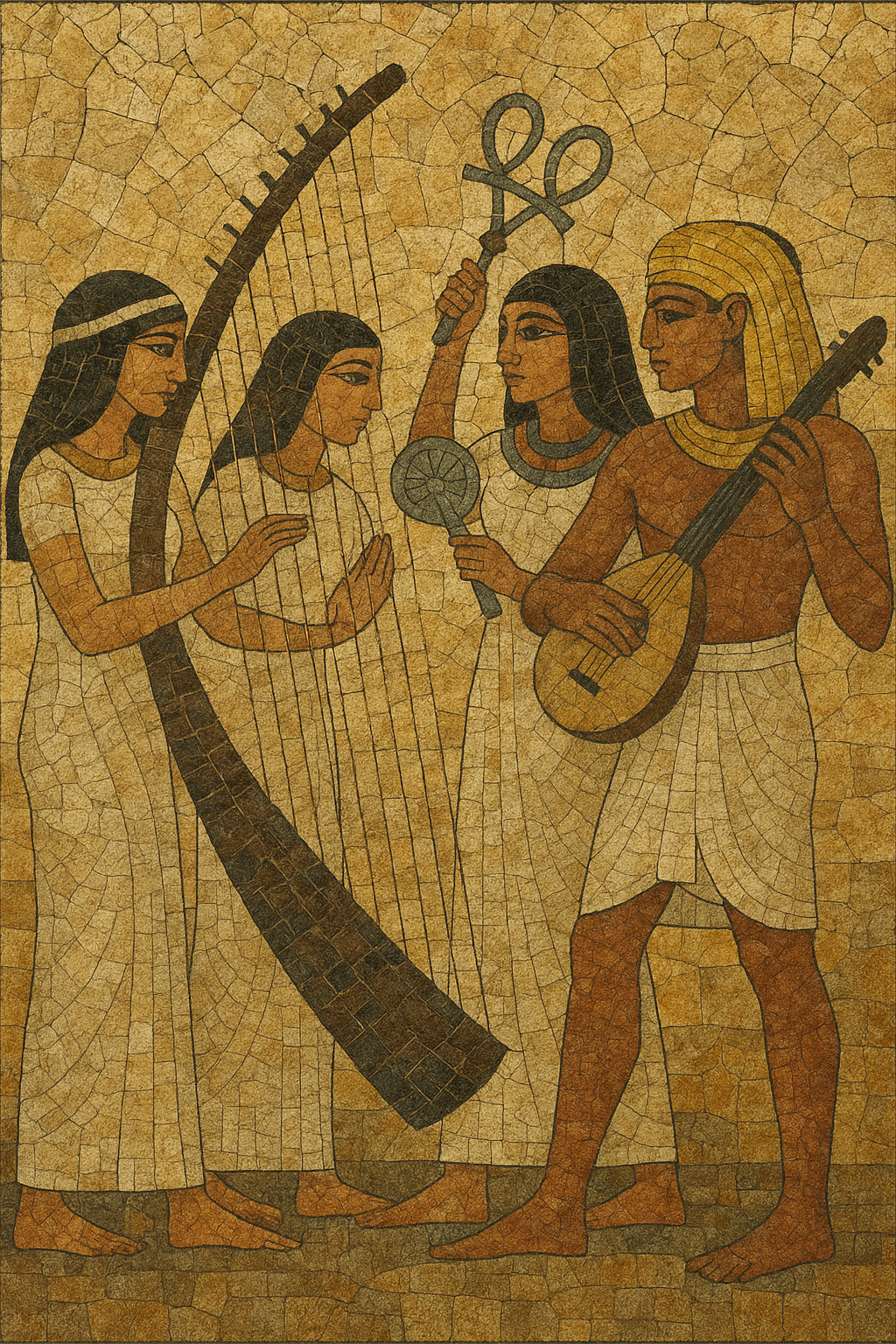

It was integral to ritual, kingship, festivals, funerary rites, banquets, and daily life. Iconography and texts show ensembles of singers, dancers, and instrumentalists serving temples and courts, as well as professional entertainers in domestic feasts.

Characteristic instruments include arched and angular harps, lyres, long‑necked lutes (introduced later from the Levant), end‑blown flutes and double pipes, double‑reed pipes, natural trumpets, frame and goblet drums, hand clappers, and two emblematic ritual rattles: the sistrum and the menat. Textures were largely monophonic or heterophonic with drones, and rhythm was strongly cyclic. While no definitive notation survives, melodic practice was likely modal, with small intervals, stepwise motion, and ornamental inflection guided by voice and instrument.

Archaeological depictions from the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom (c. 3000–2200 BCE) reveal harps, clappers, flutes, and ritual rattles used in palace and temple contexts. Music served as an offering to the gods and a sonic sign of royal power, with specialized roles for priest‑musicians and court performers.

By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2050–1710 BCE), texts such as the Harper’s Songs attest to a literate, reflective musical culture linking music to funerary remembrance and ethical reflection. In the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), Egypt’s contact with the Levant and wider Mediterranean enriched instrumentaria (long‑neck lutes, additional lyre types, double‑reed pipes). Nebamun’s tomb paintings and other scenes show banquet ensembles of singers, lutenists, harpists, dancers, and hand‑clappers performing cyclic rhythms.

Music permeated temple liturgy (with shemayet singer‑priestesses, sistrum and menat rattles in the cults of Hathor, Amun, and Isis), royal and civic festivals, processions, and funerary rites, as well as work songs and domestic entertainment. Performance was generally monophonic or heterophonic, with ornamented unison lines and drones. Rhythm was repetitive and processional, supporting dance and ritual movement.

No staff‑like notation survives, so scale systems and exact tuning are inferred from instruments, depictions, and comparative traditions. Melodies likely used limited ranges, stepwise motion, and flexible intonation shaped by voice and instrument rather than fixed tempered systems. The absence of harmonic functional progressions suggests a modal approach with drones and parallel intervals.

Under the Ptolemies (332–30 BCE), Greek and Egyptian practices coexisted: double‑pipes (aulos) appear alongside traditional Egyptian harps and rattles in ritual and theater. After antiquity, aspects of Egyptian ritual soundworlds persisted most clearly in Coptic Christian chant and ceremonial percussion, and—through Egypt’s centrality in the Arab world—contributed indirectly to the broader Arabic maqām tradition.

Use arched or angular harp (Celtic harp can substitute), lyre, a fretless long‑neck lute or oud (for later New Kingdom color), end‑blown flute or ney, soft double‑reed (shawm/oboe family) where appropriate, natural trumpet, frame or goblet drum, hand clappers (castanets/wood blocks), and shakers or tambourine to emulate the sistrum and menat. Keep textures predominantly vocal‑led with instruments doubling and ornamenting the melody.

Write modal, stepwise melodies with limited ambitus (a 5th to an octave). Favor drones (tonic or tonic–fifth) and heterophony: different performers vary and ornament the same line simultaneously. Avoid functional harmony; instead, sustain a tonal center with occasional neighboring tones and ornaments (slides, mordents, grace notes).

Build cyclic grooves using repeated patterns in 2s and 3s (e.g., 2+2+3, 3+3+2). Let hand drums and clappers mark the cycle while sistrum‑like shakers articulate downbeats and processional accents. Structure pieces as processional ritornellos, responsive chants (call‑and‑response), or strophic hymns with instrumental interludes.

Set invocatory or poetic texts in concise lines. For authenticity, draw inspiration from translated sources such as the Harper’s Songs, the Hymn to the Nile, and temple hymns to Amun or Hathor. Use antiphonal exchanges between a soloist and a small chorus; include ululations or vocables for festive moments.

Use flexible, un‑tempered intonation guided by the voice and instrumental resonance rather than fixed equal temperament. Emphasize warm, woody timbres (harp, lyre, flutes) and crisp ritual percussion (sistrum/menat emulations). Add natural reverberation (stone or plastered spaces) to evoke temples and tomb chapels.