Alternative folk (often shortened to alt-folk) applies the DIY ethos, experimental textures, and boundary-pushing songcraft of alternative and indie scenes to the acoustic foundations of traditional folk. It preserves storytelling, organic timbres, and intimate vocals, but departs from strict tradition through unconventional arrangements, eclectic influences, and non‑standard production choices.

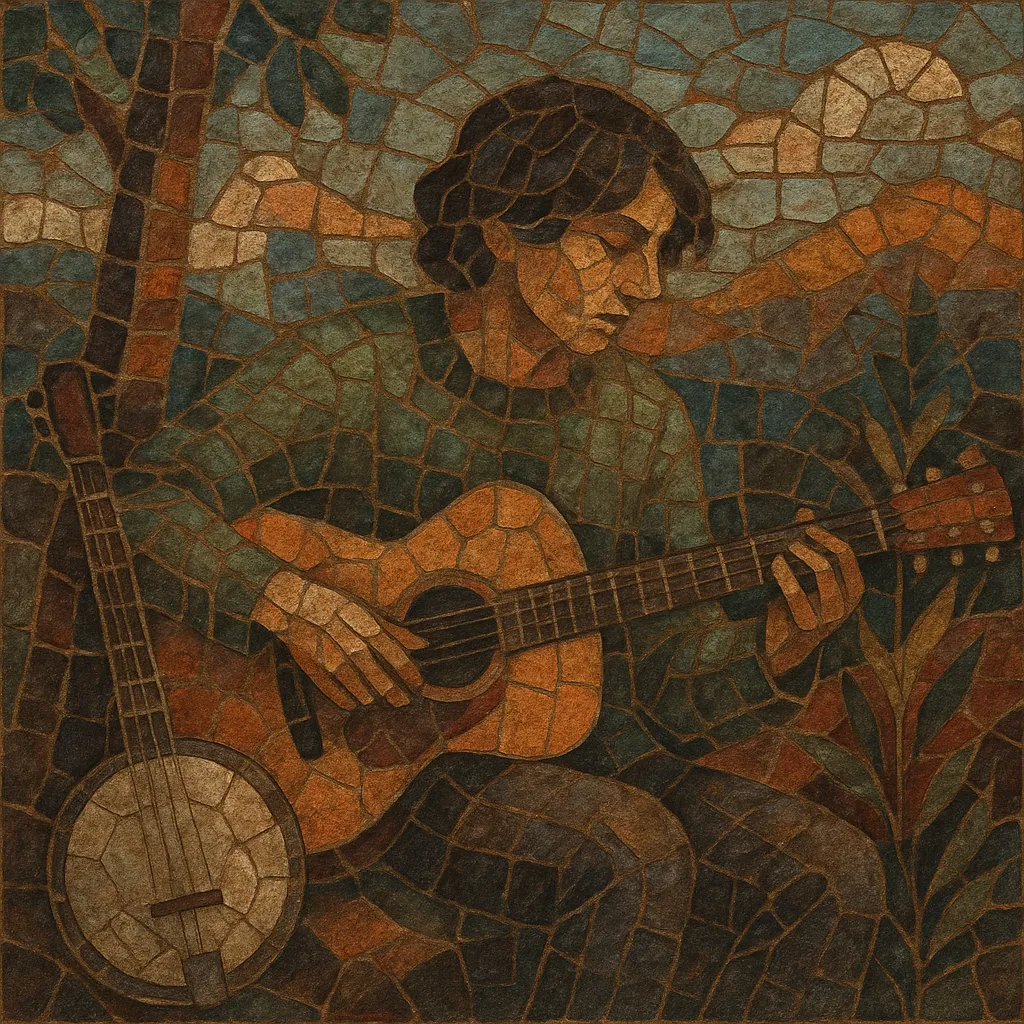

Typical recordings blend acoustic guitar, banjo, or strings with tape hiss, room noise, unusual percussion, or subtle electronics. Lyrics lean toward introspective, surreal, or obliquely political themes, and song structures can be more fluid than verse‑chorus norms. The result is folk’s warmth and narrative sensibility refracted through an alternative lens.

Alternative folk coalesced in the United States during the 1980s as songwriters from punk, post‑punk, and underground indie circles embraced acoustic instruments while keeping a DIY attitude and a taste for off‑kilter lyricism. The anti‑folk scene in New York served as a crucial incubator, challenging coffeehouse formalism with humor, abrasion, and experimentation.

In the 1990s, alt‑folk became more visible as college‑radio and indie labels supported intimate, lo‑fi recordings and stark, confessional songwriting. Artists fused folk fingerpicking with alternative rock aesthetics—close‑miked vocals, minimal drum kits, and tape-worn textures—helping distinguish the style from classic folk revivalism and from slick adult‑contemporary singer‑songwriting.

The early 2000s saw a wave sometimes dubbed “New Weird America,” in which alt‑folk intersected with psychedelic folk, free‑form experimentation, and outsider pop. Harps, chamber strings, odd meters, and field recordings became common, while some artists incorporated gentle electronics, cementing alt‑folk’s reputation for porous boundaries.

In the 2010s, alt‑folk aesthetics informed the broader indie‑folk boom: sparse acoustic textures, intimate vocals, and literary lyrics reached larger audiences. The style now comfortably overlaps with chamber folk and folktronica, while retaining its core: storytelling, acoustic roots, and alternative production choices that privilege mood, texture, and personal voice.

Start with an acoustic foundation: steel‑string guitar, nylon guitar, banjo, mandolin, upright bass, piano, or harmonium. Add color with strings (violin/viola/cello), hand percussion, found sounds (handclaps, foot stomps, household objects), or subtle electronics (pads, granular textures, tape loops).

Use primarily diatonic progressions but introduce color via modal interchange (borrowed IV minor, flat VII), suspended chords, or open tunings (DADGAD, Open D/G) to create drones and resonant overtones. Melodies can be close to speech rhythm—intimate and restrained—or folk‑modal (Dorian/Mixolydian) for a rootsy hue.

Keep tempos moderate to slow; favor gently pulsing strums, broken arpeggios, or fingerpicking patterns (e.g., Travis picking). Occasional odd meters (5/4, 7/8) or rubato passages add an alternative edge without overwhelming the song.

Prioritize narrative, imagery, and personal reflection. Blend everyday detail with surreal or symbolic lines. Avoid clichés by using specific sensory images (place names, weather, small gestures). Allow ambiguity; alt‑folk often invites interpretation rather than telling listeners exactly what to think.

Embrace intimacy. Close‑mic vocals, minimal compression, and natural room reverb convey presence. Don’t fear tape hiss or gentle noise floors—they can serve the aesthetic. Layer acoustic parts sparsely; introduce one unusual texture (toy piano, bowed cymbal, modular pad) to signal the "alternative" character.

Use verse‑chorus with evolving arrangements, or try verse‑only strophic forms, through‑composed mini‑suites, or instrumental codas. Let dynamics grow organically—start solo, then add strings or harmony vocals in later verses.